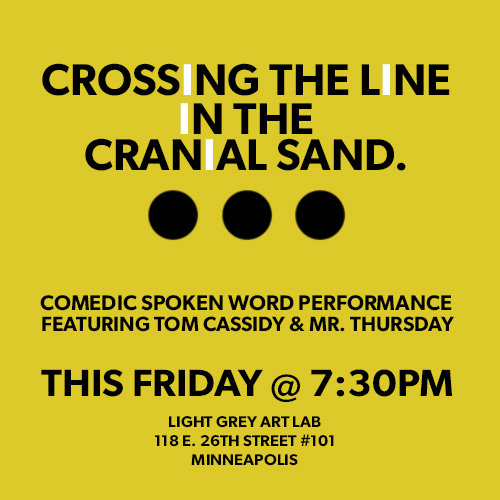

This week we're hosting a

guest performance/lecture by Tom Cassidy, a local artist and expert on mentalism, mail art, slam poetry and linguistics. His fascinating and unusual work has been featured globally, from publications to performances. To get a little taste of what's to come, we asked Tom a few questions about his work and process.

Can you share a little bit about your history and involvement with the literary and poetry communities?

I’ve been an active mail-artist since 1970 and have accumulated over 30,000 pieces of correspondence art–pre-zine-culture smallpress, postcards, poems, collages, drawings, pass-&-add sheets, etc. And I’ve been a contributor to dozens of alternative, underground and visual poetry smallpresses, from

Modern Correspondence to

Popular Reality, from

Shavertron (a mostly serious zine based on cult-sci-fi-guy Ray Palmer’s belief that ancient aliens inhabit inner earth) to Joe Bob Brigg’s

Drive-In Newsletter, from

Lost & Found Times to the

Portland Scribe (for which I wrote a column about correspondence art in the 70s). I co-founded the performance poetry troupe The Impossibilists and have shown or read at over one hundred galleries, festivals, bars and colleges; my works have been in over 200 shows blahblahblah (I didn’t participate for a resumé or batting average). I also hosted Open Mics for 25 years and heard over 12000 writers and folksingers as a type of penance.

When were your first introduced to mail-art, and what did you find most interesting about the culture of exchange? Can you also explain how it works?

I was first exposed to mail-art when I met by Dana Atchley (Ace Space Company) at California College of Arts & Crafts in 1973. Dana, a road-tripping documentarian of America’s cultural underbelly, was an early social networker and plugged me into The Eternal Network, which was what the great untethered hum of mail-artists was then called. I mailed drawings and manifestoes to folks whose work I saw in

FILE magazine and slowly developed my own network with those whose works I enjoyed (including visual poet John Bennett with whom I still correspond and collaborate). It was exhilarating, satiric, bolt-loosening, subversive and fun and it still is, though nowadays I only regularly correspond with about two dozen artists.

I only noticed decades later that my network has a heavy bias towards concrete/visual poetry, stuff that’s anti-other stuff, and humor. As to how it all works? Inefficiently, with personal touches all over the connections, slowly, with carrier pigeons; and “with a lick, because a kiss wouldn’t stick.”

Is the work produced from this project your own? Everyone’s? A Collective? The last person to receive the piece?

Every mail-art piece is different or same-but-different and most envelopes I receive contain several folded visual poems or drawings and/or a very limited edition zine and/or a collage or a copy of a collage you add to then forward, maybe an artstamp sheet or a handwritten letter. I’ve received everything from a McDonald’s cheeseburger (address and postage on its yellow paper wrapper), to a bottle to throw in the ocean, to a rock in the mail. But mostly I receive mad chaotic missives from people I’ll never meet; it’s like being LinkedIn by your most aberrant gene. Many pieces are collaborations but, though they’re signed by all who add to the piece, who-did-what isn’t specified or consequential. I’ve kept pieces I was “supposed to” forward and have forwarded pieces I’d never want. Even decades ago, it wasn’t the wild west, it was and is what’s really going on among artists when they’re not getting all artsy, careering around and hustling for grants.

You said that most of the artists in the mail-art community are only known by their aliases or pen names. Is there a sense of achievement, seniority, or leadership amongst the community,or is all work just work?

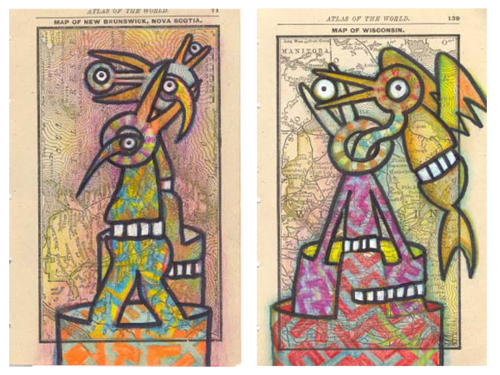

Originally the aliases added to the playfulness of the network and occasionally the name-itself was a large portion of the exchange (for example, correspondents named Occupant, Greet-O-Matic, RayJohnson’s New York CorreSpongeDance School). Though the movement (which of course was then an anti-movement) was an art-for-art’s-sake effort to share expressions outside the worlds of commerce and institutionalized art, the aliases weren’t bids for anonymity so much as alter-egos that superseded regular ground rules of communication and created exchanges in which gender, age, “art-status,” and, significantly, whereabouts didn’t matter. I was Space Angel for several years, before assuming the name I still use, Musicmaster. Over the years however I’ve participated in dozens of projects as other personalities, even using the names/alter-egos of other artists. I enjoy being an agitator, outsider and prankster because most things in our world need shaking down; and when I collaborate with (often drawing on top of works by) others, I feel a bit more anchored and part-of-something than I do when creating in isolation.

There is, alas, now a history of mail-art, with Ray Johnson as deity and a number of mail-art history books (I’ve contributed chapters to three of them), and hundreds of extensive museum and university archives. It may not be true that we all age into respectability, but many of us do, and too many of us embrace that.

What is your creative process like for making work?

I’ll read a piece about this–when I sit down to write I just draw–at the February 2 talk. I love process far more than product, and am so prolific that I occasionally knock out a homer. Much of my work is fueled by a mix of caffeine and beer.

Can you explain your connection between what you do on stage and what you do on paper, how your approach to art-making and language relate?

Though I enjoy performing what might be best described as stand-up poetry with trapdoors to hell, I’m very self-conscious on stage and play a character that’s crafted and rehearsed to seem more off-the-cuff and comfortable than I really am. Writing to escape the logic and baggage of language is difficult for me; no matter how randomized or chaotic my experimental pieces get, I usually feel the quicksand of linear logic, narrative, a need to explain things to a judge. My drawings are less inhibited; and while I sincerely want people to enjoy what I do when I’m on stage, I’m far, far less concerned about what they make of my artworks.